Introduction

In recent years, the rise of advanced analytics and AI has transformed what businesses expect from their data pipelines. Traditional business intelligence asked data engineers to design and build scalable pipelines, which would deliver static reports and dashboards, but today’s AI-driven workflows demand dynamic, conversational interactions that can retrieve and reason over data, on the fly. Companies can see the tangible edge things like generative AI and RAGs are giving their competitors, and there is a rush to integrate similar solutions in their own businesses.

Data engineers therefore are facing a new challenge. In addition to designing these traditional pipelines for classic reporting and fast queries, data engineers must now also be ready to feed AI models with high-quality data in real time. Even if an organization is not ready to integrate such solutions immediately, data engineers need to be mindful that AI and machine learning will very likely be integrated downstream at some point in the near future.

This new challenge is by no means easy. A study conducted by MIT Technology Review Insights and Snowflake found that 78% of businesses felt unprepared for generative AI due to poor data foundations, even though the vast majority, around 72%, planned to integrate AI in the pursuit of increased efficiency and innovation. This juxtaposition can lead to the ever-present “garbage in, garbage out” mantra. A lack of high-quality data leads to a lack of high-quality AI and ML solutions.

The future of successful analytics solutions will be dependent on organizations effectively aligning their data architecture with these new demands. In this article, I will discuss how to build data pipeline solutions that deliver lightning-fast query performance and are “AI-ready,” covering storage design, query optimization, and integration of AI-focused data layers. I will also highlight why these practices are valuable for businesses seeking a competitive edge.

Aligning Data Storage with Data Types and Access Patterns

A foundational step before beginning to build any pipeline is to assess what data is currently available, then match each data type and intended usage pattern to the right storage technology. Structured data, which consists of highly organized information like transactions, customer records, etc., is best housed in relational databases or data warehouses that enforce schemas and ACID (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability) properties. Systems like PostgreSQL, MySQL, or cloud warehouses like Amazon Redshift and Snowflake excel at complex SQL queries and consistency.

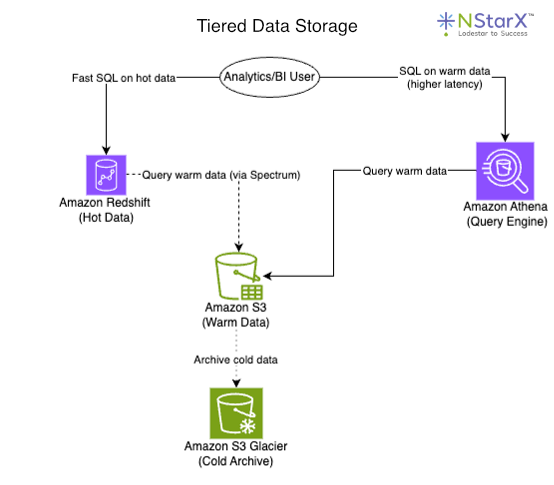

In AWS, a common strategy is to design a tiered storage solution. Tiered storage is the strategy of keeping “hot” frequently accessed structured data in Redshift, while offloading less-frequently used “warm” data to a data lake on Amazon S3, that can be queried via Redshift Spectrum or Athena, and finally “cold” data in AWS Glacier for data that is infrequently accessed but cannot be deleted. For example, an e-commerce company might keep its transactional and customer data in a warehouse, like Amazon Redshift, for fast analytics, but might keep data older than three years in Glacier if it is not readily required. The reason being that “hot” storage is much more costly than “warm” or “cold” storage; therefore, designing a solution based on data speed and/or frequency needs can be essential in optimizing computational expenditure.

Figure 1.

Redshift provides high-performance SQL on recent data, whereas Spectrum and Athena let you run SQL directly on S3 files for older or less critical data. The reason this is a cost-effective approach is because S3 storage is much cheaper than Redshift. The main trade-off being that both Athena and Spectrum queries have higher latency. That being said, this design ensures that each dataset lives in a storage layer optimized for its access frequency and structure. Hot, mission-critical data stays in a low-latency store, whereas warm and cold data is kept in inexpensive storage but remains queryable when needed. Such separation also allows independent scaling of compute and storage.

For semi-structured or NoSQL data, other storage options come into play. Many organizations ingest high-volume event streams or JSON documents that don’t fit neatly into a relational schema. These might be stored in scalable NoSQL databases, log aggregation services, like CloudWatch Logs, or key-value stores like Amazon’s DynamoDB, MongoDB, or Cassandra, which can handle flexible schemas and high write/read throughput. Likewise, user activity logs often land in a cloud data lake or a log database and are later parsed into structured forms as needed. The guiding principle is to choose storage optimized for the data’s format and query needs. For example, time-series telemetry data might reside in a time-series database, while graph-oriented data, like social networks or product knowledge graphs, might be stored in a graph database.

Unstructured data such as text documents, images, audio, etc., usually cannot be directly inserted into rows and columns, but these types of data are becoming increasingly more crucial for AI analysis. The typical approach is to store raw unstructured files in an object store or data lake and use specialized indexes for retrieval. Object storage services like S3, Azure Data Lake, and Google Cloud Storage, combined with NoSQL or search indexes like Elasticsearch/OpenSearch or MongoDB, are commonly used for unstructured data. For instance, a company’s PDF documents or support tickets could be kept on S3; then an indexing service like OpenSearch or a vector database makes the text inside those files searchable. The key is that unstructured data is preserved in a cheap, scalable store and augmented with metadata or embeddings that enable quick queries.

By aligning storage choices with data characteristics, a pipeline can achieve both efficiency and flexibility through relational stores for structured data, data lakes for large or unstructured data, and specialized databases for niche use cases. Each dataset is thus “in the right place,” which paves the way for high performance retrieval later on.

Ensuring Quick Query Performance

Designing for quick query speed means planning how data will be organized and accessed to minimize latency. One vital practice is to format and partition data in a way that accelerates queries. In analytical data lakes, for example, storing files in columnar formats like Parquet and compressing them can dramatically improve scan performance. Columnar storage allows query engines to read only the needed rows/columns instead of entire datasets, while compression reduces I/O by scanning fewer bytes. Along with columnar format, partitioning datasets by common filters, such as dates, regions, common identifiers, etc., further boosts query speed, since the engine can skip irrelevant partitions. These optimizations mean analysts querying a petabyte-scale data lake can get results in seconds rather than minutes, as less data is read from disk. Data warehouses similarly benefit from clustering or sorting keys that co-locate related data, and from proper indexing on frequently used columns.

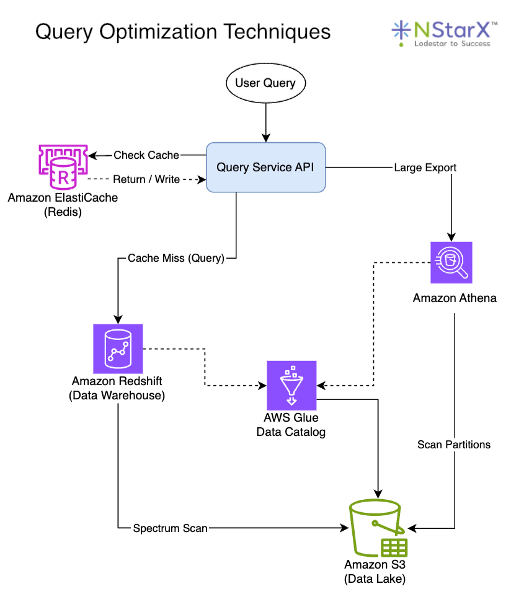

Figure 2.

Beyond storage layout, architectural patterns and tools can be employed to achieve sub-second query responses. One strategy is to pre-aggregate or cache readily needed results. OLAP cubes, materialized views, or summary tables can store the results of expensive computations, such as daily sales totals by region, so that queries retrieve a small, precomputed result instead of having to scan raw data each time. Many modern pipelines include an in-memory cache layer, such as Redis, in front of databases, to serve ultra-fast responses for repetitive queries or API calls. For example, a dashboard that shows today’s KPI metrics might hit a Redis cache that is updated every few minutes, avoiding direct database queries on each page load. Another tactic is denormalizing or duplicating data for read speed, which essentially means trading some storage space for faster reads. While normalization is ideal for OLTP systems, analytical queries often benefit from flattened tables that eliminate expensive joins.

Cloud data warehouses tackle the performance challenge with elastic scalability. They can distribute queries across many nodes or even spin up additional compute on demand. For instance, Amazon Redshift’s concurrency scaling can transparently add extra cluster capacity within seconds to handle spikes of hundreds of concurrent queries, maintaining low latency, even under heavy load. The ability to auto-scale or use serverless query engines, means the pipeline can meet high demand, without performance degradation, albeit at a higher cost for the extra resources. Notably, there is often a surcharge on serverless equivalents of computational time, as hyperscalers charge a premium for that “always on and available” service. Designing pipelines for concurrency and peak loads is crucial if hundreds of users or applications might query data simultaneously. A general rule of thumb when determining peak throughput for future-proofing is to plan for roughly 5-10× your current max throughput.

With all that being said, it’s important to note the trade-offs between query speed, data freshness, and cost. This is commonly referred to as the “trade-off triangle.” When trying to achieve low latency, fast queries, and low cost, you can usually only optimize for two, but not all three simultaneously. Achieving real-time, sub-second query responses on large, constantly updating datasets typically requires significant investment in infrastructure and engineering. Low latency and fast complex queries often demand high-performance compute clusters, in-memory processing, and meticulous tuning, which are all extremely expensive in their own right. Keeping every metric updated to the last second and instantly queryable might involve streaming pipelines, continuous ETLs, and memory-heavy storage engines, driving up cloud bills. If budget is a concern, a company might compromise by updating some aggregates hourly instead of in real time, or by allowing slightly slower queries on very large datasets while caching only the hottest subset. The key is to identify which use cases truly need millisecond interactivity and engineer the pipeline to meet those with specialized fast paths, while handling other analytics in a more cost-efficient batch or “warm” manner.

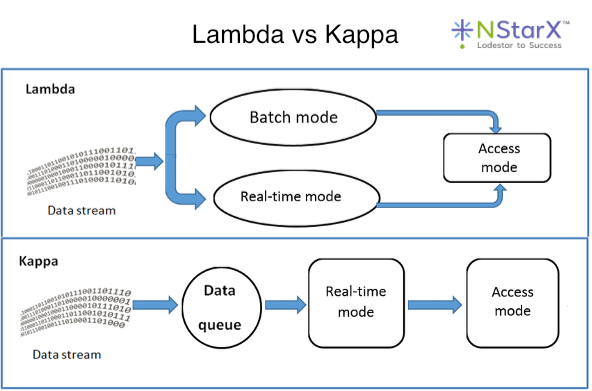

Figure 3. (Source: Research Gate)

In practice, as is the case with most solutions, a hybrid approach often works best. Many organizations implement a Lambda or Kappa architecture, where a streaming pipeline handles real-time data for urgent queries, while a parallel batch pipeline processes the bulk of data for historical or less time-sensitive analysis. This way, a “speed layer” delivers instant insights on recent events, backed by a comprehensive but slightly latent “batch layer” that ensures accuracy and completeness. In contrast, the emergence of Lakehouse platforms has been blurring the line between hot and warm analytical workloads. Technologies like Databricks or Apache Iceberg on S3 allow near-real-time queries on lake data by providing warehouse-like indexing and ACID capabilities on the data lake.

Regardless of the specific tools, focusing on data organization and smart caching or aggregation strategies is pivotal to achieve interactive query performance. When done right, end users can slice through billions of records in seconds, enabling data-driven decisions without unnecessary latency.

Building an AI-Ready Data Architecture

Quick queries alone are not enough in an era where AI and machine learning workloads are becoming routine. An “AI-ready” data pipeline extends beyond traditional warehouses and reports; it incorporates new layers and processes to feed AI models with the right data, context, and features. A core principle here is that data needs to be not just collected, but also connected and enriched for AI consumption. This often means creating a semantic layer or knowledge fabric on top of raw data so that AI systems can understand relationships and context, not only raw figures.

One approach gaining traction is the use of knowledge graphs to represent key business entities and their interrelationships in a flexible graph structure. A knowledge graph stores data as nodes (entities) and edges (relationships), explicitly encoding how things are connected. An example of this would be a graph that links a customer to the products they purchased, or connects a patient to all their medical records. Knowledge graphs excel at capturing complex relationships and enabling reasoning or inference over data. For instance, a financial institution might build a graph of accounts, transactions, and owners to detect fraud patterns via network connections. Popular graph databases such as Neo4j, AWS Neptune, and TigerGraph can store this web of linked data, and importantly, they make it queryable in ways that traditional SQL struggles with. You can traverse paths, such as finding all customers two hops away from a known fraudster and uncover insights via graph algorithms. In the framework of AI, knowledge graphs provide explainability and a structured context. An AI system can use the graph to understand, for example, that Customer A is related to Account B, which is related to Transaction X, enabling deeper reasoning than raw tables would ever allow. Gartner has identified knowledge graphs as a “critical enabler” for successful generative AI, underscoring their growing importance.

Another complementary technology is the vector database, which addresses a different need: making unstructured data and content easily searchable by meaning. Vector databases store data as high-dimensional vectors (embeddings) that capture the semantic essence of text, images, or other media. Instead of exact keyword matching, a vector DB lets you query for similar concepts. In simple terms, a vector database is designed to store embedding vectors and answer similarity searches such as “find me documents semantically similar to this query,” which is crucial for applications like semantic search, recommendations, or retrieval-augmented generation (RAGs).

For example, in a customer support AI, a vector DB could retrieve past FAQ answers most relevant to a user’s question, even if the wording differs, by comparing embedding vectors. This is what powers the RAG approach. An AI assistant first pulls relevant knowledge from a vector index, then uses it to formulate a more accurate answer. Indeed, retrieval-augmented generation pairs a language model with a search over a knowledge base, so that the AI can fetch up-to-date policies, documents, or records to ground its answers. The “knowledge base” in a RAG could be a vector DB of documents or a combination of vector search and a knowledge graph. Open source and commercial options for vector stores are numerous, making it accessible for teams to integrate semantic search into their pipelines.

Rather than choosing between a knowledge graph and a vector database, many organizations are finding value in using both in tandem, as they serve different purposes. The vector database provides fuzzy semantic retrieval, which is great for unstructured text, images, and finding “similar” items, while the knowledge graph provides structured logical retrieval and reasoning, which is great for enforcing business rules and relationships. Used together, they can significantly enhance an AI’s capabilities. In practice, this might look like an AI system first using a vector search to fetch content related to a query, then using a knowledge graph to filter or contextualize those results via known relationships. Enterprises are indeed moving toward such hybrid stacks that combine vector indexes and knowledge graphs, aligning their data management with AI use cases. For example, documents might be embedded for semantic lookup, while at the same time key facts from those documents are extracted into a knowledge graph with an ontology defining how concepts relate. This way, an AI assistant querying the data can leverage both the “fuzzy” match and the “precise” match to retrieve the best answer with reasoning traceability.

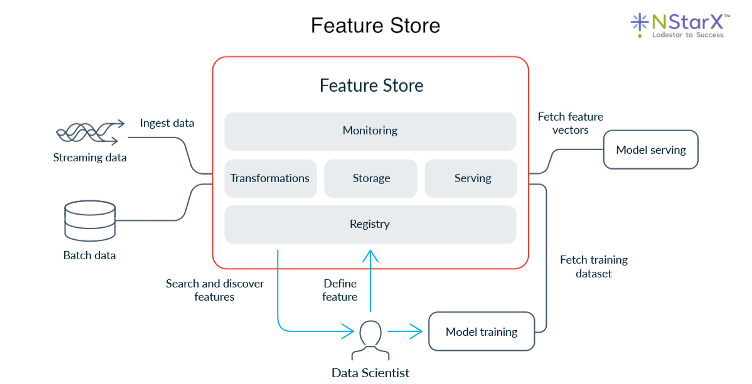

Figure 4. (Source: Feast)

Beyond search and retrieval, being AI-ready also means preparing to feed machine learning models with the data they need in a reliable, scalable manner. This is where the concept of a feature store often comes in. A feature store is a specialized data repository that stores engineered features for ML models and serves them for both training and inference consistently. In a traditional pipeline, data scientists might manually transform raw data into features. For example, a data scientist could aggregate user activity over the past 7 days, and use those in model training; but operationalizing that for live predictions can be error-prone, as you’d have to replicate the logic in production.

A feature store essentially centralizes this process. The pipeline computes feature values and stores them, along with metadata about their definitions, sources, entities, and timestamps, and when a live model needs a feature vector for a new input, it pulls the latest available features from the store. This ensures the model sees the same definition of features in production as in training, avoiding training-serving skew. For instance, if “average spend in the last 30 days” is a feature used to train a fraud detection model, pipelines can continuously or frequently update that value for each customer and write it to the feature store, which then serves it with low latency to the model during inference.

Feature stores have become a necessary component to ensure data pipelines are AI-ready, making sure that data engineering and data science workflows remain in sync. When designing an AI-ready pipeline, integrating a feature store, or at least a consistent feature engineering layer, is recommended if you plan to deploy ML models at scale. This includes setting up pipelines to compute features, handle temporal correctness so models don’t peek into future data, and store historical feature values for reproducibility.

Finally, an often-underestimated aspect of AI readiness is data governance and cataloging. AI systems are extremely sensitive to data quality. Biases or errors in training data can lead to faulty models, and a lack of lineage makes it hard to trust AI outputs. Modern pipelines address this by incorporating robust monitoring, metadata management, and governance from the ground up. It’s advisable to maintain a data catalog or metadata repository, tracking what data exists, its schema, lineage, and owners. This not only helps analysts find and understand data, but also enables AI to access the right data with proper context. For example, an AI agent can use metadata to decide which internal database to query for a given question.

Implementing data quality checks at each pipeline stage is also vital in ensuring that anomalies are caught before they corrupt a machine learning model’s input. Additionally, as enterprises plan to expose more data to AI, unifying semantic definitions across the organization becomes key. This might involve developing an enterprise ontology or common data model that both relational and AI systems adhere to.

All these efforts contribute to what some call an “AI-ready knowledge fabric”, meaning a rich, well-organized layer of data, with relationships, context, and governance, that AI and analytics tools can tap into securely. The payoff is that data scientists and AI applications spend less time wrangling unclear data and more time delivering insights since AI outputs become more readily trusted by business users as they are grounded in a transparent data foundation.

Conclusion

Designing data pipeline solutions for both quick query speed and AI readiness requires a holistic approach to data architecture. It starts with storing each dataset in the appropriate system. This means using relational warehouses or lakehouses for structured transactional data to enable fast SQL analytics, leveraging data lakes and NoSQL stores for large-scale semi-structured and unstructured data to retain flexibility and cost-efficiency, and tiering data into hot, warm, and cold layers so that query workloads are always hitting the optimal storage medium.

On top of this foundation, engineers must implement techniques to turbocharge query performance. From file format optimizations and partitions in big data environments, to indexes, materialized views, and caching for operational analytics, to scalable cloud services that can handle concurrent bursts without slowing down. These optimizations ensure that users can get answers from the data with minimal waiting, which is crucial in an age where real-time insights can create competitive advantages.

Equally important is preparing the pipeline for AI workloads. That means integrating new components such as knowledge graphs and vector databases that enable AI to retrieve and interpret information by understanding context, meaning, and connections. It also means providing consistent, high-quality data to machine learning models via feature stores and rigorous data validation so that AI predictions are accurate and dependable. The best-in-class pipelines today are those that treat data as a continual lifecycle. Raw data is collected and preserved, refined into structured warehouses for analysis, enhanced with semantic layers for AI, and constantly governed and monitored for quality.

Businesses that invest in these robust data pipelines reap tangible benefits. They get instantaneous analytics for decision-making and personalized customer experiences thanks to speedy queries over well-organized data. They also unlock new AI-driven capabilities, from intelligent assistants that can answer free-form questions using corporate knowledge, to predictive models that proactively improve operations. In short, an AI-ready, high-performance data pipeline turns data into a strategic asset rather than a bottleneck.

Achieving all of this is certainly an engineering challenge, but it is increasingly becoming a prerequisite for innovation. As data volumes and AI opportunities grow, pipeline architectures must evolve in step. The effort, though, is worthwhile in the long run. A thoughtfully designed pipeline will empower analysts to explore data more easily and enable AI systems to deliver value with confidence. By matching data types to the right storage, optimizing for query speed, and weaving in the needed AI-centric layers, data engineers can ensure their infrastructure is not only meeting today’s needs but is adaptable for the future. In the end, organizations that master this balancing act will be positioned to harness data for both real-time insights and intelligent automation, a crucial advantage in the data-driven era.

References

- Fluree. “GraphRAG & Knowledge Graphs: Making Your Data AI-Ready for 2026.” https://flur.ee/fluree-blog/graphrag-knowledge-graphs-making-your-data-ai-ready-for-2026/

- Skyvia. “Structured vs Unstructured Data: Complete Guide 2025.” https://skyvia.com/learn/structured-vs-unstructured-data

- Cadium. “Redshift Spectrum vs. Athena: Understanding AWS’s Data Query Solutions.” https://medium.com/@cadium828/redshift-spectrum-vs-athena-understanding-awss-data-query-solutions-aa8aa7fc3b6d

- AWS Big Data Blog. “ETL and ELT design patterns for lake house architecture using Amazon Redshift: Part 1.” https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/big-data/etl-and-elt-design-patterns-for-lake-house-architecture-using-amazon-redshift-part-1/

- Cube Blog. “The Trade-Offs of Optimizing Data Pipelines: Data Latency, Cost and Query Speed.” https://cube.dev/blog/the-trade-offs-of-optimizing-data-pipelines-data-latency-cost-and-query

- Nitin Kaushal. “Vector Databases vs Knowledge Graphs: Which One Fits Your AI Stack?” https://medium.com/@nitink4107/vector-databases-vs-knowledge-graphs-which-one-fits-your-ai-stack-816951bf2b15

- Snowplow. “Implementation Guide: Building an AI-Ready Data Pipeline Architecture.” https://snowplow.io/blog/building-an-ai-ready-data-pipeline

- Tech Monitor. “Survey reveals 78% of businesses unprepared for gen AI due to poor data foundations.” https://www.techmonitor.ai/digital-economy/ai-and-automation/survey-reveals-78-of-businesses-unprepared-for-gen-ai-due-to-poor-data-foundations

- Feast. “What is a feature store?” https://feast.dev/blog/what-is-a-feature-store/

- ResearchGate. “Comparison of Lambda and Kappa architectures.” https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Comparison-of-Lambda-and-Kappa-architectures_fig1_341479006

- AWS Documentation. “Concurrency scaling – Amazon Redshift.” https://docs.aws.amazon.com/redshift/latest/dg/concurrency-scaling.html

- AWS Documentation. “Optimize data – Amazon Athena.” https://docs.aws.amazon.com/athena/latest/ug/performance-tuning-data-optimization-techniques.html

- AWS Documentation. “Partition your data – Amazon Athena.” https://docs.aws.amazon.com/athena/latest/ug/partitions.html

- AWS. “Amazon S3 Storage Classes.” https://aws.amazon.com/s3/storage-classes/

- AWS Documentation. “Managing Lake Formation permissions.” https://docs.aws.amazon.com/lake-formation/latest/dg/managing-permissions.html

- AWS Documentation. “Data discovery and cataloging in AWS Glue.” https://docs.aws.amazon.com/glue/latest/dg/catalog-and-crawler.html

- AWS. “Amazon DynamoDB Features – NoSQL Key-Value Database.” https://aws.amazon.com/dynamodb/features/

- AWS Documentation. “Vector search – Amazon OpenSearch Service.” https://docs.aws.amazon.com/opensearch-service/latest/developerguide/vector-search.html

- AWS Documentation. “k-Nearest Neighbor (k-NN) search in Amazon OpenSearch Service.” https://docs.aws.amazon.com/opensearch-service/latest/developerguide/knn.html

- AWS. “Amazon Bedrock Knowledge Bases.” https://aws.amazon.com/bedrock/knowledge-bases/

- AWS Documentation. “Create, store, and share features with Feature Store (Amazon SageMaker).” https://docs.aws.amazon.com/sagemaker/latest/dg/feature-store.html

- AWS Documentation. “Query Apache Iceberg tables – Amazon Athena.” https://docs.aws.amazon.com/athena/latest/ug/querying-iceberg.html

- AWS. “Graph and AI – Amazon Neptune.” https://aws.amazon.com/neptune/graph-and-ai/

- AWS. “Time-Series Database – Amazon Timestream.” https://aws.amazon.com/timestream/

- Apache Iceberg Documentation. “AWS.” https://iceberg.apache.org/docs/latest/aws/

- AWS Big Data Blog. “Build data lineage for data lakes using AWS Glue, Amazon Neptune, and Spline.” https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/big-data/build-data-lineage-for-data-lakes-using-aws-glue-amazon-neptune-and-spline/